eMMUlate: Breaking (some of) the TI-Nspire CX II's security

Disclaimer: This work does not enable cheating, nor does it break the chain of trust. It is intended solely to enable emulation of the CX II in Firebird.

The Backstory

Earlier this year, I was debating over getting either a Casio CG-50 or a TI-Nspire for my AP Calc BC exam. To me, the ability to mod and mess around with my stuff is an important factor, and upon a quick google search, the Nspire had ndless, which allowed me to run assembly programs. Hence obviously, I purchased the Nspire.

To my dismay, however, my calculator was too new to run ndless(it shipped with OS ver. 6.0). Unfortunately, the project seemed abandoned, with no updates in over 4y. Desperate, I started looking for exploits myself, hoping to port it. Eventually, I was added to the dev group, and Ndless r2020 was born.

My drive for digging into the calc didn't end there, however. I eventually discovered that Firebird, the emulator for all Nspires, couldn't emulate the CX II. "Incomplete bootrom detected.", it would complain. Intrigued, I looked into what exactly this "incomplete" meant, and it turned out to be this hidden region of the BootROM from 0x27800 to 0x28000, which was nicknamed keys.

While most of BootROM is normally readable and dumpable using a tool such as polydumper, this elusive region will dump out all zeros. It was understood that it would only be unmasked under a very specific set of conditions, conditions only known to TI and etched into the silicon.

The Analysis

By disassembling the dumped BootROM using Ghidra, is it quite trivial to find out that function 0x39C is responsible for reading the keys. However, it directly loads the keys into the 3DES MMIO block. The keys never touch SDRAM!

It is obvious that there is some sort of check on the Program Counter(PC), since both the OS and the Bootloader never attempt to read that region by themselves. Instead, they call 0x150(which eventually calls 0x39C) to directly load the keys to 0xC8010000, the location of the 3DES MMIO block. They then use it directly to encrypt and decrypt the files. This is a direct indicator that keys can only be read from BootROM, and maybe only specifically those instruction addresses.

Furthermore, according to research done by Vogtinator, the hardware is needed to be in an extremely specific state. MMU needed to be off and some undocumented bits in CP15 needed to be set. The 3DES engine seems have its registers be write-only, and reading would only produce 0x5D5AEA97(not keys). All to say, TI did not cheap out on the security... Or did they...?

Wait a second...

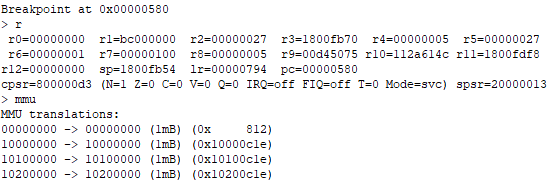

While stepping through the instructions in Firebird(which could at max load bootloader without keys), I noticed something odd. The stack pointer was assigned to 0x1800FB54. This address does not exist in physical memory, since SDRAM is only from 0x10000000 to 0x14000000. This meant that the MMU was actively in use. This contradicted with what Vogtinator said previously so I checked it out myself:

A multi-billion dollar company such as TI could surely have foreseen that if the MMU is on, it is extremely simple to do some MMU mapping shenanigans to hijack where keys are written. Obviously, right?

This is a funny pattern that I've noticed across the entire Nspire code. TI seems to fortify their house with bricks but leaves their front door wide open. Of course, there could still be a check to ensure that 0xC8000000 was identity mapped, but you are reading this post so you know where that is going :D

Looking at my (admittedly very ugly) code for the exploit, the starting just creates the program's own page tables so I can freely change memory mappings.

uint32_t pt_addr = ((uint32_t)page_table_buffer + 0x3FFF) & ~0x3FFF;

uint32_t *page_table = (uint32_t *)pt_addr;It goes on to identity map most peripherals, SRAM and RAM. However, with regards to 0xC8000000:

uint32_t des_va_idx = 0xC8000000 >> 20;

page_table[des_va_idx] = (0x13000000 & 0xFFF00000) | (0b11 << 10) | (0 << 5) | 0 | 0b10;This maps 0xC8000000 to 0x13000000, so any writes to the 3DES engine ends up at 0x13010000. Therefore, after somehow exiting from 0x39C, we can just read off this address to get keys.

The Stack Trap

When I originally attempted to call 0x39C, it would not return only on hardware. Therefore, I though I could exploit this piece of code:

0000076c 60 10 8f e2 adr r1,DAT_000007d4 = E12FFF1Eh

00000770 00 40 91 e5 ldr r4,[r1,#0x0]=>DAT_000007d4 = E12FFF1Eh

00000774 10 00 2d e9 stmdb sp!,{r4}

00000778 3d ff 2f e1 blx sp

For some reason, it attempts to load a bx lr into the stack and jump to it. I don't exactly understand why, but this is before

00000788 b3 fe ff eb bl FUN_0000025c which was causing the problems with not returning. Hence, by setting the stack to an extremely precise position at the edge of accessible memory, it is possible to get back control right after keys are read a couple instructions earlier. For this, I create my own exception vectors:

uint32_t vec_addr = ((uint32_t)vector_buffer + 0xFFF) & ~0xFFF;

uint32_t *vectors = (uint32_t *)vec_addr;

uint32_t cpta_vec_addr = ((uint32_t)cpta_vectors_buffer + 0x3FF) & ~0x3FF;

uint32_t *coarse_vec_table = (uint32_t *)cpta_vec_addr;

// build vector table

printf("Setting up vector table at 0x%08lX...\n", vec_addr);

for (int i = 0; i < 8; i++) vectors[i] = 0xE59FF018;

vectors[12] = (uint32_t)data_handler; // The one we care aboutAnd map it to 0xFFFF0000 . I also enable high vectors, so the ARM CPU knows to jump to my vectors instead of BootROM's:

// high vector enable

uint32_t sctlr;

asm volatile("mrc p15, 0, %0, c1, c0, 0" : "=r"(sctlr));

sctlr |= (1 << 13) | (1 << 0);

asm volatile("mcr p15, 0, %0, c1, c0, 0" :: "r"(sctlr));Setup

Next, we perform some setup for the exploit:

void perform_exploit_setup(void) {

printf("Performing exploit setup...\n");

// these are the observed conditions that 0x39c is in when called via bootloader.

volatile uint32_t *usb_top = (volatile uint32_t *)0xB0000000;

usb_top[0x100 / 4] = 0;

usb_top[0x1C0 / 4] = 0;

// extensive setup, refer to the source for the full function

printf("Exploit setup complete.\n");

}This is just setting a list of conditions on the hardware(such as shutting off the DMA, the USB controllers etc) that the CPU expects at this point. Without this, the CPU will just return 0x0s. Most of this was just observed by using Firebird. Finally, we can call trigger_next_key();, which just jumps into SVC mode(in case we were previously in abort mode), resets the trap stack(which catches the stmdb at 0x774) and jumps to call_rom39c.

0x39C takes in 4 paramters. r0 is ignored and overwritten. r1just dictates which part of the switch will be used(we want 0x5), r2 decides which "set" of keys we are loading and r3 sets the 3DES engine to either encrypt or decrypt mode. By iterating r2 for each call, we can extract the entire hidden region. However, it seems like only 0x27, 0x3d, 0x25, 0x2d are ever used. Hence, my program only extracts those:

__attribute__((naked))

void call_rom39c(uint32_t __attribute__((unused)) sram_stack, uint32_t __attribute__((unused)) r2_val) {

asm volatile(

// r0 = sram_stack

// r1 = r2_val

"mov r12, r0 \n\t" // r12 = sram_stack

// Save caller registers on *current* stack

"stmfd sp!, {r4-r11, lr} \n\t"

// Save old SP

"mov r4, sp \n\t"

// Switch to trap stack

"mov sp, r12 \n\t"

// Save old SP on trap stack

"stmfd sp!, {r4} \n\t"

// Setup ROM args

"mov r2, r1 \n\t" // r2 = r2_val

"mov r0, #0x5 \n\t"

"mov r1, #0x5 \n\t"

"mov r3, #0x1 \n\t"

// Call ROM 0x39C

"ldr lr, =0x0000039C \n\t"

"blx lr \n\t"

// Restore SP

"ldmfd sp!, {r4} \n\t"

"mov sp, r4 \n\t"

// Restore caller registers and return

"ldmfd sp!, {r4-r11, lr} \n\t"

"bx lr \n\t"

);

}The Finale

Here's the final flow:

- We call

0x39C - It writes keys to what it thinks is

0xC8010000 - The keys end up at

0x13010000 - CPU attempts to

stmdb, and ends up in our no-access region - DATA ABORT!

This calls our own exception vectors, which copy the keys to a different location and moves onto the next set of keys:

void c_handler(EXCEPTION_TYPE type, uint32_t lr, uint32_t sp) {

if (type == DATA_ABORT) {

volatile uint32_t* des_regs = (volatile uint32_t*)0x13010000;

for (int i = 0; i < 6; i++) {

extracted_keys[current_key_idx][i] = des_regs[2 + i];

}

// ... print keys ...

current_key_idx++;

trigger_next_key();

} else {

// ... error handling ...

}After all keys are extracted, we can display the keys to the user. I have chosen to do this via a QR code, allowing the user to easily use a tool to inject keys into their keyless bootrom.

(It seems like there's some sort of issue with my nginx reverse proxy and https, causing the above image to not load in correctly. You might need to click on it.)

Both QRs are the same, this is just the result of weird VRAM mapping that TI does and me being too lazy to handle it correctly. Furthermore, since this program messes up the state of the device pretty bad, I found it easier just to reset instead of attempting to restore and exit back to the Nspire UI.

And there you have it. (some of) the TI-Nspire CX II's security is broken with an UNPATCHABLE exploit. Good job TI :)

I'd appreciate if you could star the project on Github below

Exploit: https://github.com/satyamedh/eMMUlate

Injector: https://satyamedh.github.io/eMMUlate_injector